The History of Business Law at Yale

Simeon E. Baldwin, Professor of Constitutional and Mercantile Law, Corporations and Wills, 1869-1919

Simeon Eben Baldwin (1840-1927), a native of New Haven and alumnus of Yale College (1861), studied law at the Law School from 1861-62 and was a professor at the Law School for fifty years, as well as the Law School’s Treasurer for decades. In the Nineteenth century, the Law School faculty were not salaried positions, and Simeon Baldwin was also a leading practitioner, legal scholar, jurist, and Connecticut statesman. He was the governor of Connecticut from 1911-15, after having served as justice and then chief justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court. He was also founder and president of the American Bar Association, president of the Association of American Law Schools, the American Social Science Association, the American Political Science Association, the American International Law Association, and the American Historical Association.

William K. Townsend, Edward J. Phelps Professor of Law, 1881-1907

William Kneeland Townsend (1849-1907) was an alumnus of both Yale College (1871) and the Law School (1874). Considered “one of Yale’s most brilliant sons” and “one of the most distinguished men in Connecticut,” Townsend was appointed to the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut in 1892, and elevated to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in 1902. During this period, Judge Townsend lectured on contracts at the Law School, and published a History of American Law of Patents and Trademarks, Copyrights, and Admiralty.

At the Law School, a professorship was established in his honor in 1925 and a library fund in 1942.

Arthur L. Corbin, William K. Townsend Professor of Law, 1903-43

Arthur L. Corbin (1875-1967), an alumnus of the Law School (1899), became the school’s first full-time professor in 1903, and remained a force at the School for over five decades. Corbin was a giant of American contract law and an intellectual father of the Legal Realist movement that blossomed at Yale in the 1930s. His comprehensive treatise Corbin on Contracts, in updated versions, still serves as a standard reference for judges and lawyers.

Typical of Corbin’s scholarship—and central to the Realist project—was the effort to probe whether important legal principles did in fact inhere in the cases that ostensibly supported them. A famous example was Corbin’s demonstration that “consideration” was not always required to make a contract binding. His recognition that “reliance” often supplied an alternative basis to consideration for contract enforcement was ultimately embodied in section 90 of the Restatement of Contracts.

Edward A. Harriman, Lecturer in Administrative Law, 1906-17

Edward Avery Harriman (1869-1955) came to the Law School from Northwestern, where he was a Professor of Law and faculty Secretary. Harriman was a prominent contract law scholar who corresponded frequently with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. on the theory of contracts. The correspondence began when Harriman sent Holmes a copy of his law review article, “The Nature of Contractual Obligation,” 4 Nw. L. Rev. 97 (1895), that drew upon Holmes’ ideas. That article was the first chapter of Harriman’s treatise, Elements of the Law of Contracts (1896), which he later expanded into a multi-volume work, The Law of Contracts (1901).

William R. Vance, Lafayette S. Foster Professor of Law, 1910-12, 1920-38

William Reynolds Vance (1870-1940) was dean of the University of Minnesota Law School before returning to Yale in 1920. Vance was a leading insurance law scholar of his day. His casebook Cases on the Law of Insurance, first published in 1914, remained in print (in various editions) for nearly forty years. Vance also served as general editor of West Publishing’s American Case Book series from 1912-35.

Wesley N. Hohfeld, Southmayd Professor of Law, 1914-18

Wesley N. Hohfeld (1879-1918), came to Yale from Stanford in 1914, and remained until his untimely death at the age of 39. In his brief career, he published articles on a wide range of topics, including corporate law, partnership law, conflict of laws, trusts, and jurisprudence.

Hohfeld’s most lasting contribution to legal scholarship was his two-part article “Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning,” 23 & 26 Yale L. J. 16 & 710 (1913 & 1917), which was republished as a book several times by Yale University Press (1st ed. 1923). In it, Hohfeld analyzed the notions of legal “rights” and “duties,” breaking them down into a framework of claims, privileges, powers, and immunities on the one hand, and corresponding duties, no-rights, liabilities, and disabilities on the other

Thomas W. Swan, Professor of Law and Dean, 1916-27

Thomas Walter Swan (1877-1975) graduated from Yale College in 1900 and attended Harvard Law School, where he was Editor-in-chief of the Harvard Law Review. He was brought to the Law School as Dean in 1916 from private practice in Chicago and a lectureship at the University of Chicago Law School. The subjects of Dean Swan’s research and teaching were bankruptcy and corporations. He remained the School’s dean for slightly over a decade, until his appointment to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

Although Dean Swan’s career on the bench was far longer than his time at the Law School, being an active jurist through his service as Chief Judge of the court from 1951-53, he was as instrumental as Simeon Baldwin was decades earlier in the formative years of the Law School’s history and is considered one of the School’s great deans.

Edward S. Thurston, Southmayd Professor of Law, 1919-29

Edward Sampson Thurston (1876-1948) was a professor at the Law School for a decade, having been recruited from the University of Minnesota. Thurston, a leading contracts scholar, was best known for his casebooks, Cases in Quasi-Contract, which first appeared in 1916, and Cases on Restitution, which was published in 1940. A graduate of Harvard Law School who was considered a “traditionalist” by the Law School’s Legal Realists, Thurston left Yale for his alma mater in 1930.

Karl N. Llewellyn, Assistant Professor of Law, 1919-20, 1922-25

Karl Nickerson Llewellyn (1893-1962) enrolled in the Law School after being wounded while serving as a volunteer in the German army in World War I. He was Editor-in-chief of the Law Journal 1918-19. After graduating in 1918 and receiving an advanced law degree (J.D.) in 1920, serving as an instructor at the Law School during his graduate study, Llewellyn returned to Yale in 1922 as a member of the faculty. He left Yale for Columbia after only three years, but his early Legal Realist work was to inform the rest of his career, particularly his contributions to the drafting of the Uniform Commercial Code.

With the possible exception of Jerome Frank, Llewellyn was the most prominent and important of the Yale Legal Realists of the 1920s and 1930s.

Wesley A. Sturges, Edward J. Phelps Professor of Law, 1924-61

Wesley Alba Sturges (1893-1962), an alumnus of the Law School (1923), was one of the most popular teachers on the faculty of his day and served as dean of the Law School from 1945-54. He retired from Yale in 1961 to become dean of the University of Miami Law School.

A prominent figure in Yale’s Legal Realist movement of the 1930s, Sturges wrote on a range of commercial topics, including bankruptcy, arbitration, and credit transactions. In a well-known article, “Legal Theory and Real Property Mortgages,” 37 Yale L. J. 691 (1928), Sturges (with Samuel Clark) demonstrated that doctrinal distinctions between “lien theory” and “title theory” had no impact on how courts ruled in mortgage disputes. His casebook, Cases and Materials on the Law of Credit Transactions (1936), embodied the Realist functional approach to law, organizing cases in the way a practicing lawyer would approach problems and combining what were previously separate courses in bankruptcy, mortgages and suretyship, into one course on the credit system.

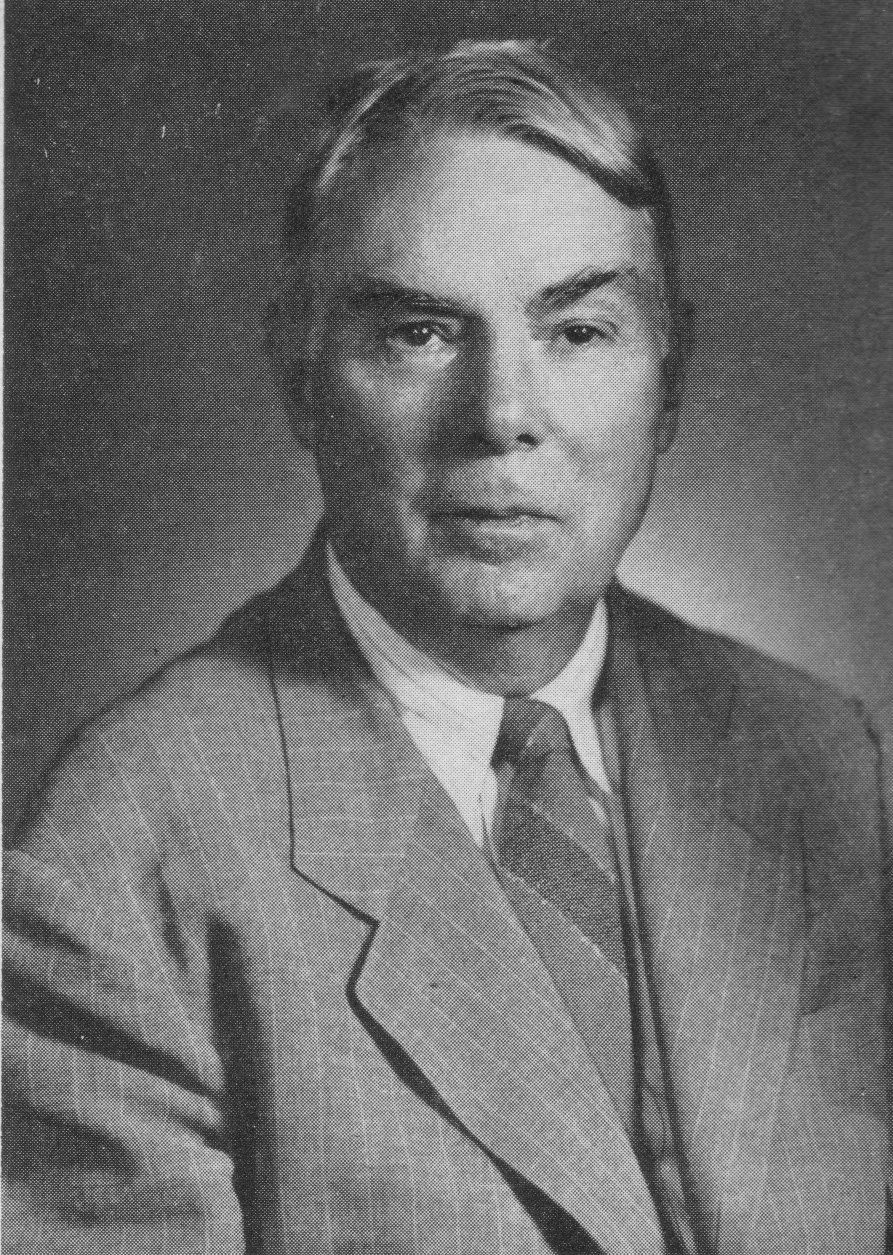

Roscoe T. Steffen, Professor of Law, 1925-49

Roscoe Turner Steffen (1893-1976), a Law School alumnus (1920), was on the faculty for over two decades. A member of the Legal Realist movement, Steffen was a leading agency law scholar, and taught the first-year agency course at Yale. Steffen published on a broad range of commercial law topics, and his innovative 1933 casebook, Cases on the Law of Agency, was one of the first to attempt to integrate modern problems of business organization into the agency materials.

Alexander H. Frey, Assistant Professor of Law, 1926-30

Alexander Hamilton Frey (1898-1981) was an alumnus of Yale College (1919) and the Law School (1921; J.S.D. 1925). He was one of the talented Yale graduates hired by Dean Swan in the 1920s under Arthur Corbin’s strategy of appointing a “crop of young instructors” who had trained at Yale. He left Yale upon his marriage to a student in 1930, and joined the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania Law School in 1932. At Penn he taught labor law as well as corporate law, and played a leading role in the creation of the Philadelphia branch of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Frey’s views concerning legal education were imbued with Yale’s Realist tradition. He advocated introducing law students to real world legal problems rather than abstract cases (such as the world of credit transactions and insurance) and to the social sciences, in order to develop empirical knowledge that could bear on resolving legal problems. Frey authored several successful casebooks, including Cases and Statutes on Corporations (1st ed. 1935), an innovative book in the Realist tradition that included materials in addition to cases, was organized on functionalist principles by business transaction rather than legal doctrine, and combined subjects typically treated in separate courses, partnerships and corporations.

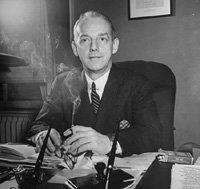

William O. Douglas, Sterling Professor of Law, 1928-36

William Orville Douglas (1898-1980) had a short but remarkably productive career as an academic. Lured away from the University of Chicago in 1928, Douglas was at Yale for only five years before embarking on his long career in the public sector. In 1934 he started commuting between New Haven and Washington, D.C. to direct a study on creditor protective committees in corporate insolvency reorganizations for the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Douglas took a formal leave of absence in 1936 when he became a commissioner of the agency, and resigned in 1937 when he was appointed chairman of the Commission. In 1939, he was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court, where he served until he retired in 1975.

Walton H. Hamilton, Southmayd Professor of Law, 1928-48

Walton Hale Hamilton (1881-1958) was one of the intellectual leaders of the Legal Realist movement at Yale. An economist but not a lawyer, Hamilton applied the insights of institutional economics to legal contexts, producing many classic critiques of legal formalism. In works such as “The Ancient Maxim Caveat Emptor,” 40 Yale L. J. 1133 (1931), “Affectation with a Public Interest,” 39 Yale L. J. 1089 (1930), and “The Path of Due Process of Law,” 48 Ethics 269 (1938), he showed how legal concepts that had evolved in specific historical and social contexts could lead to surprising and undesirable outcomes when removed from context and generalized into universal legal principles. Hamilton also undertook industry studies to show how wages and prices were not set by market forces as understood by neoclassical economists but rather depended on social and historical contexts, that resulted in noncompetitive wages and prices.

W. Underhill Moore, Sterling Professor of Law, 1929-47

William Underhill Moore (1879-1949) came to Yale from Columbia in 1929. An expert in commercial bank credit and business organizations, Moore was one of the intellectual leaders of the Legal Realist movement at Yale and a pioneer in the use of social scientific methods in legal research.

Like his Yale contemporary Karl Llewellyn, Moore maintained that judges often applied non-legal norms—especially norms of commercial behavior—in deciding cases. Of the Realists, Moore was the most dedicated to the ideal of scientific objectivity. n a famous 1929 study, “An Institutional Approach to the Law of Commercial Banking,” 38 Yale L. J. 703 (1929), Moore (with Theodore S. Hope, Jr.) attempted to explain and predict banking law decisions that did not appear to derive from existing legal rules by determining the extent to which the facts of the case deviated from normal banking practice. In addition, in a series of articles with Gilbert Sussman, Moore undertook an empirical survey of actual banking practices in discounting notes.

Later scholars have criticized Moore’s empirical studies for their primitive methodology, but his core notion about the importance of empiricism in legal research has largely become conventional wisdom.

Harry A. Shulman, Sterling Professor of Law, 1929-54

Harry Shulman (1903-55) came to Yale in 1929. He was appointed the dean of the Law School in 1954, but died only a year later. Although he contributed to torts and administrative law scholarship, his best-known work involved labor contracts.

Shulman has been described as “one of the most influential people in the history of American Labor arbitration.” He served on the National War Labor Board during World War II, and later served for many years as umpire of the labor agreement between Ford Motor Company and the United Automobile Workers. His 1949 casebook, Cases on Labor Relations, on which he collaborated with an economist, was the first book on arbitration of collective bargaining disputes and, in the functional approach of the Legal Realist tradition, was organized by the types of disputes that might arise in the life of a labor contract.

Dean Shulman’s 1955 Oliver Wendell Holmes Lecture, “Reason, Contract, and Law in Labor Relations,” 68 Harv. L. Rev. 999, remains one of the most frequently-cited law review articles. His vision of the limited and restrained arbitrator has remained influential to this day.

Thurman W. Arnold, Lafayette S. Foster Professor of Law, 1930-31, 1931-38

Thurman Wesley Arnold (1891-1969) was one of the most prominent Legal Realists at Yale in the 1930s. Arnold was recruited to the Law School faculty in 1930, and remained at the school until 1938, when he was appointed Assistant Attorney General in charge of the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice.

During his years on the faculty, Arnold authored numerous law review articles and became one of the most prominent Legal Realists through publication of two best-selling books, written for a lay audience, The Symbols of Government (1935) and The Folklore of Capitalism (1937).

As a pioneering leader of the Antitrust Division, however, Arnold was perhaps the most aggressive trust-buster in the division’s history. He restructured the division to emphasize an anti-monopoly strategy with “consumer welfare” (competitive prices) as the goal, rather than a reduction in the concentration of power per se.

Arnold served in the Antitrust Division until he was appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit in 1943. In 1945, he left the bench and founded the Washington, D.C. law firm that still bears his name, Arnold & Porter.

Friedrich Kessler, Sterling Professor of Law, 1935-39, 1947-70

Friedrich Kessler (1901-1998) fled Nazi Germany in 1934 and came to Yale, where he remained until 1970 except for a stint at the University of Chicago Law School from 1938-47. Kessler was a self-described Legal Realist, and one of the world’s leading contracts scholars.

Kessler described the Legal Realist’s task as “constantly testing out the desirability, efficiency and fairness of inherited legal rules and institutions in terms of the present needs of society.” “Natural Law, Justice and Democracy—Some Reflections on Three Types of Thinking About Law and Justice,” 19 Tul. L. Rev. 32, 52 (1944). Much of Kessler’s most important work consisted of “testing out” the doctrine of “freedom of contract.”

In his celebrated article, “Contracts of Adhesion—Some Thoughts About Freedom of Contract,” 43 Colum. L. Rev. 629 (1943), Kessler maintained that Eighteenth century concepts of freedom of contract were inadequate to the realities of modern industrial economies. Through standardized contracts, he contended, parties with stronger bargaining power – in particular, large corporations – could impose their will on individuals, and courts were reluctant to give up the language of freedom of contract, even when they decided in favor of the weaker party, creating doctrinal confusion, instead of recognizing the modern contracting context and modifying the concept of freedom of contract to fit the contracting circumstances.

Randolph E. Paul, Visiting Sterling Lecturer, 1937-43

Randolph Paul (1890-1956) was one of the architects of the federal income tax. An advocate of the expansion of federal taxes during World War II, he served first as an informal advisor to the Treasury Department on tax issues in the late 1930s and early 1940s. He assumed a full time position after the attack on Pearl Harbor, becoming General Counsel to the Treasury in August 1942. During the years when he was lecturing at the Law School, in addition to engaging in private tax practice, serving as a director of the Federal Reserve Bank in New York and providing advice to the Treasury Department, he published a series of influential works on federal taxation, including Studies in Federal Taxation (1937, 1938, 1940), and Federal Estate and Gift Taxation (1942). As Treasury General Counsel, he advocated a broad income tax, both as a revenue producer to finance the war effort, and as a tool for regulating the economy. He contended that an income tax expanded to include the middle class was more equitable, as well as more reliable as a revenue stream to meet war needs, than a national sales tax, an alternative being promoted by members of Congress, among others, at the time.

In 1944, Paul left the Treasury Department to found the New York law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison.

James William Moore, Sterling Professor of Law, 1938-74

James William Moore (1905-1994) received a doctorate from the Law School (1935) and joined the faculty in 1938 after two years at the University of Chicago Law School. Moore was the leading bankruptcy law scholar of his generation. He edited the authoritative treatise in the field for decades, the multi-volume Collier on Bankruptcy (orig. pub.1898), beginning in 1938 when he assumed the position of the work’s Editor-in-chief at the time of the enactment of the Chandler Act, which was a major rehauling of the bankruptcy laws.

Moore’s other publications in the field include Moore’s Bankruptcy Manual (1939) and the casebook, Debtors’ and Creditors’ Rights: Cases and Materials, written with Vern Countryman, which was first published in 1947 and went through four editions by 1975.

Moore authored the leading treatise not only on bankruptcy law, but also on civil procedure, an unusual accomplishment. Along with Dean Charles E. Clark, Moore was one of the lead drafters of the new “trans-substantive” Federal Rules of Civil Procedure in the 1930s. Moore wrote extensive commentaries on the new rules, culminating in the definitive guide to the rules, the 34-volume Moore’s Federal Practice, which he personally updated well into the 1980s.